About ten years ago, when Boris Johnson was Mayor of London, a meeting was organised to discuss planning matters in the bulbous shape of the City Hall building beside Tower Bridge. During a break, Johnson conversed with a representative from the Wandsworth Society and commended the view from the windows, praising the Gherkin as a beautiful iconic building. When he was told that unfortunately it would likely be soon completely obscured by most of the skyscrapers he had recently permitted, he chuckled. For the man who campaigned in 2008 against what he called Ken Livingston’s “phallocratic towers” and vowed not to endorse skyscrapers if residents objected to them, it must have been ironic indeed.

For many critics, that could summarise the approach adopted by politicians towards the skyline of the British capital: a lack of consideration, an absence of vision and a very personal interest in some cases.

Labour or Conservatives, all are to blame

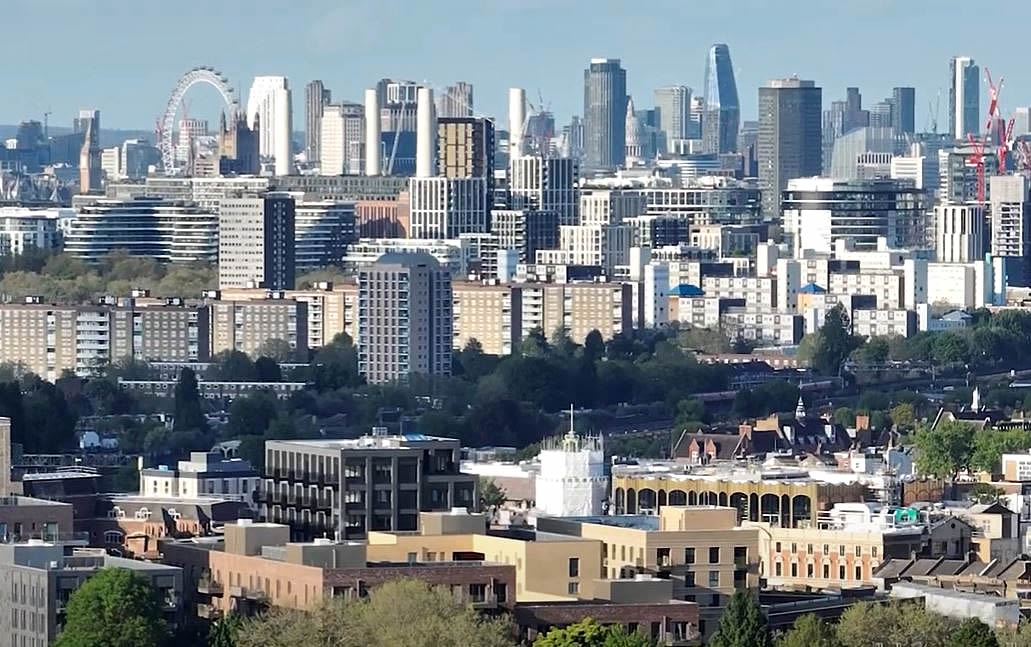

Two decades ago, London, which had been dominated for three centuries by St Paul’s Cathedral (111 metres), had a relatively low skyline, with only a few notable tall buildings.

The Millbank Tower (118 metres) was erected in 1963 near Parliament (nearly at the same time as Centre Point in Central London built in 1966 at 117 metres) and the BT Tower emerged the following year at 177 metres. Fast forward another 20 years, and the NatWest Tower (now called Tower 42) was completed in 1980 in the City of London standing at 183 metres. Eleven years later came One Canada Square (235 metres) in Canary Wharf, but it was further away, a project initiated under Margaret Thatcher and seen as a business center to mimicking La Defense on the outskirts of Paris.

While most changes in the French capital occurred in the 70s (La Defense, the cluster of towers in the west along the river Seine, the Montparnasse Tower) under the impulse of President Georges Pompidou, a proponent of modern architecture, the construction of tall building has been restricted and mostly stopped immediately after. The recent resurgence with few towers on the outskirts of Paris has been met with ferocious outcry and French politicians have pledged to prevent further incursions into the skyline (although one knows what is often said about promises from politicians…).

London only began its adolescent crisis at the start of the new century with the election of Ken Livingstone as Mayor of the city. However, unlike Paris, it shows no signs of halting, and many now consider it to be spiralling out of control. From Livingstone to Boris Johnson to Sadiq Khan, from Labour to Conservatives and back to Labour, the policy has remained the same: build tall, build massively… and disregard objections.

In 2003, during his initial term as Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone attended the MIPIM exhibition in Cannes, in the South of France. MIPIM is an international event showcasing the largest number of development projects and sources of capital globally. The headline in Property Week summarised the exhibition’s highlights as: “Champagne, canapés, networking, business leads, and London mayor Ken Livingstone“. The Sunday Times reported that, during one of the parties organised beside the event, Livingstone “hosted a private dinner for 11 property developers at a villa [rented for more than £2,000 a day by Montagu Evans, a firm of property consultants that regularly submits planning bids to the mayor]“.

According to the article, Livingstone expressed his commitment to providing them with “the potential to make very good profits” within his envisioned London. He particularly emphasised the construction of towering structures, displaying a preference for greater heights. Tony Pidgley, chief executive of Berkeley Homes, found him “refreshing,” and Gerald Ronson of Heron International applauded his “vision.”

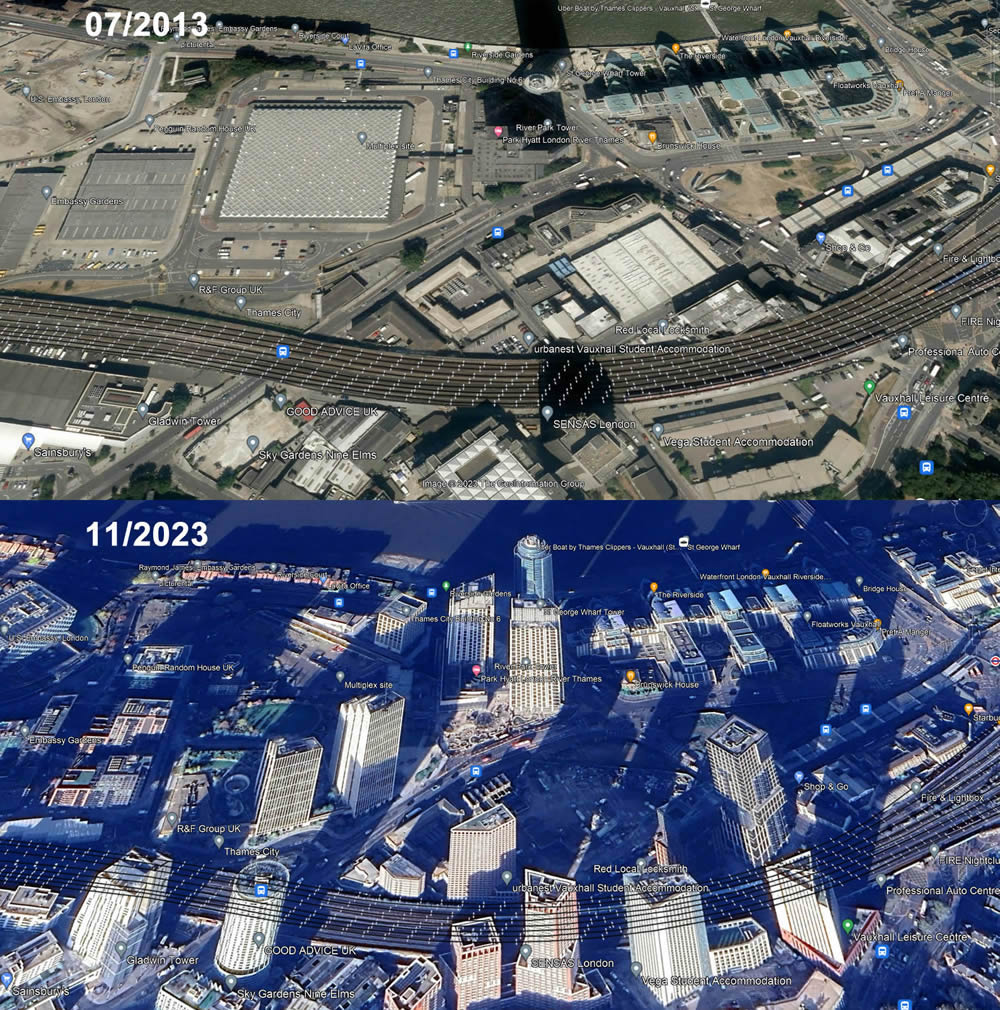

The irony might be that all the outcry that came at the time was concerning 20 projects, with half of them still to be constructed in 2008 when Ken Livingstone lost the election to Boris Johnson. When Boris Johnson left after his second term, we were talking about more than 200 schemes. And now under Sadiq Khan, the number has risen to nearly 600.

But the initial objections are still valid. Simon Jenkins, an editorial writer for The Guardian, said in 2008 that “the horizontal skyline of the capital will be transformed into a series of point blocks set in piazzas, shrinking the scale of what has always been essentially a street-based, intimate urban landscape. […] These are not communities but urban fortresses, worse than anything inflicted on London in the 60s or 70s“. He was talking about the “Walkie-Talkie”, the “Cheesegrater”, the “Pinnacle”.

Nowadays, the Pinnacle, with its complex spiraling structure, has been replaced by a much simpler design, and the tower seating in 22 Bishopsgate is just called Twentytwo. It stands at 278 metres high, or 62 storeys, just coming after the 310-metre Shard in the tallest-building-in-the-country competition.

But the fame will be short-lived, as it will soon be replaced by the Trellis, at 1 Undershaft, starting in 2024. This skyscraper (the planning application consented in 2016 was revised in August 2023 with a pile of 4 blocks instead of a long uniform block) should reach 305 metres and 74 storeys. Initial articles even claim that it would be the same height as the Shard.

The competition is on. The Leaf, at 55 Bishopsgate, should be claiming 285 metres with a tall office block (63 storey by the way, apparently here storeys are 4.5 metres high, not 3 metres as in the Wandsworth Local Plan!). This giant is meant to start construction in 2024.

There is also the Diamond with 263 metres and 56 storeys, at 100 Leadenhall, which has been approved nearly unanimously by the City of London in 2018, and which is meant to start building also in the next few years.

In comparison, the 36-story London office tower with “extensive vertical urban greening” proposed for 50 Fenchurch Street is a dwarf, with only 150 metres (but architect Eric Parry Architects is already claiming the second tallest buildings with 1 Undershaft above, he can now play a lower profile).

If the orgy of skyscrapers in the City is mostly a legacy of Boris Johnson’s era, the Shard won’t be isolated on the opposite side of the river for much longer. A new cluster of towers is fast emerging near Blackfriars bridge (apparently to the delight of the Labour leader of Southwark Council) with the Boomerang (170 metres tall – making it one of the tallest residential buildings in Europe) and the plan for 3 more skyscrapers designed by Foster + Partners with the tallest reaching 210 metres and 45 storeys above a podium.

A new proposal near Battersea Bridge in Wandsworth could be the starting point of a transformation – if approved – that would see a forest of very tall buildings extend from Battersea Bridge to Clapham Junction, making the junction with York Road and Wandsworth Town, much to the delight of property developers.

Read our articles: A new gigantic tower could be proposed for Battersea Bridge

There are still plenty of locations to build in Central London, so we should not preempt the imagination of architects. We have not yet reached the extravaganza currently populating New York with buildings up to 500 meters with flats priced in excess of $100m, echoing Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” (1927), where the privileged future elite resides in airborne pleasure structures, while the less privileged (the commuters in today’s London) endure the hardships below ground level.

Actually, we are already experimenting the concept, with the floating transparent pool located between two blocks of flats in Nine Elms, where some “happy-few” are able to show-off their privileges and tease the train commuters on their way to or from Victoria station.

In Nine Elms, you have the SkyPool for the rich, and the side entrance near the bins for those who cannot afford the luxury units.

The Skyline Campaign, when hope existed

However, some people did notice what was happening. In 2007, Simon Jenkins wrote in The Guardian:

“None of this is planned. It is urban anarchy.”

At the end of the day, perhaps the secret plan was to transform London into a little Manhattan to appeal to the US, Asia, and the Middle East, while distancing itself from continental Europe where cities have zones and rules indicating where some constructions could be appropriate. A sort of subtle “architectural” Brexit. In any case, it appeared that Londoners were not consulted about that big design, and even when they gave an opinion, they were ignored.

In 2014, the Skyline Campaign was launched, backed by the Architects’ Journal (UK’s best-selling weekly architecture magazine) and The Observer. It was set up by Rowan Moore and Barbara Weiss against the anarchy of tall buildings rising all over the city.

In an official statement signed by more than 80 architects, engineers, organisations, artists and historians, they said:

“The skyline of London is out of control. Over 200 tall buildings, from 20 storeys to much greater heights, are currently consented or proposed. Many of them are hugely prominent and grossly insensitive to their immediate context and appearance on the skyline.

This fundamental transformation is taking place with a shocking lack of public awareness, consultation or debate. Planning and political systems are proving inadequate to protect the valued qualities of London, or to provide a coherent and positive vision for the future skyline.”

They added:

“Too many of these towers are of mediocre architectural quality and badly sited. Many show little consideration for scale and setting, make minimal contribution to public realm or street-level experience, and are designed without concern for their cumulative effect and impact. Their generic designs threaten London’s unique character and identity.

Most of the proposed towers are not vital to London’s prosperity and financial wellbeing. The majority are residential, but they are neither essential to meeting housing needs, nor the best way to achieve greater densities. Their purpose is more to create investments than homes or cohesive communities. They have the potential to cause permanent damage to the city’s urban fabric and to its global image and reputation.”

And in their penultimate paragraph, they wrote a message of hope: “This damage can be stopped“.

During the same year, the think tank New London Architecture (NLA) conducted a study revealing that a minimum of 236 buildings exceeding 20 stories were already planned and in various stages such as under construction, approved, or pending approval within the capital city.

In its 2022 release (the latest one, 2023, focuses more on sustainability) NLA counted 583 tall buildings in the planning pipeline, with 341 of then currently having planning permission and awaiting construction, and a further 71 already approved at Planning Committee. In 2021, 34 towers have been completed and 109 are under construction.

Peter Murray OBE, curator-in-chief of NLA, says in his foreword to the report:

“The face of London has already changed irreversibly over the past two decades, and with a further 500 or so to come those changes will be even further reinforced.”

In a few days, we will turn another year and start 2024. Looking at that campaign wish 10 years ago and thinking about the next ten years, there is an opportunity to reflect on what has happened, what has failed, and address the fundamental question: Is it time to throw in the towel, admit that the London skyline is ruined beyond repair, and that we should forget about planning and architecture and focus on other things?

Whether it was planned is arguable, but the damage is done

It is difficult to understand why people are still raising the argument of historical corridors and views to St Paul.

For instance, there is currently a proposed 26-storey block adjacent to the Shard at London Bridge, which has yet to receive planning permission, but that has attracted criticism from people concerned with the view from St Paul’s Cathedral. A similar objection has been raised for The Leaf with Historic England saying that views of the cathedral from Waterloo Bridge are likely to be obscured by the new tower. And Historic Royal Palaces objected to the Trellis saying:

“Our principal concern is the potential visual impact that the proposed development would have on the setting of the Tower of London World Heritage Site and therefore it’s Outstanding Universal Value.”

Let’s be honest, the consideration that was still upheld by London authorities ten years ago has now gone; there is no “view” anymore. Just look carefully at the image at the top of this article and you might still notice, by chance with the camera angle, a bit of St Paul’s dome.

In 2012, Rafael Viñoly, the architect of the Walkie Talkie (and, beside, quite ignorant about history thinking that Louis the XIV was the one who transformed Paris), talked about the view from London historical buildings. He named the Tower of London but he could also have said the same on St Paul:

“The view from the Tower is already ruined”

The famous architect Eric Parry published a book in 2015 called Context in which he warned:

“An orgy of tall buildings will transform and arguably overwhelm London.”

Just a few months later, he unveiled his proposal for the Trellis as we mentioned above (initially even taller than the Shard but he was restricted by planning rules set by the Civil Aviation Authority). Therefore, what some people took as a criticism appears to be only a cold-blooded analysis of what is happening to London, with no intention to stop it but rather participate in the game.

The list of “starchitects” competing to “try” their latest concepts in London is impressive: Richard Rogers and Graham Stirk (Cheesegrater), Renzo Pian (the Shard), Rafael Viñoly (Walkie-Talkie), Arney Fender Katsalidis (the Leaf), Kohn Pedersen Fox (22/Pinnacle), Gerald Ronson (Heron Tower), Norman Foster (Gherkin), etc. But many so-called “landmarks” and “exclusive” developments can be found somewhere else in London: glass-walled homes stacked high into the air within massive glass buildings. The British capital has become a playground for town planners and architects for the last 15 years, with the opportunity to experiment in real life.

But of course, nothing could happen without the blessing of politicians who see property development and especially massive schemes as a way to express their power while getting subsidies from developers (see our article here). Oman (Heron Tower), Hong Kong (Walkie Talkie and the Diamond), China (Cheesegrater), Saudi Arabia (The Leaf), Malaysia (Battersea Power Station), Singapore, and Indonesia (the Trellis)… funding flows.

We have reached a time where nobody cares anymore. Money and personal ego are the only things that matter.

In 2016, Jenkins wrote in the Guardian:

“Livingstone and Johnson [and you might now add Khan since 2016] promoted these towers not because they cared where ordinary Londoners would live, or because they had a coherent vision of how a historic city should look in the 21st century. They knew they were planning “dead” speculations, because plenty of people told them so. They went ahead because powerful men with money and a gift for flattery just asked. It was very British sort of corruption.”

And he concluded:

“The appearance of these structures on the London horizon must rank as the saddest episode in the city’s recent history. We must live with them forever. But we shall not forget their facilitators.”

Edward Lister’s influence

And one of those facilitators, perhaps the most instrumental, is probably Edward Lister, the former Council Leader in Wandsworth (from 1992 to 2011).

When Boris Johnson became Mayor of London, he called upon Edward Lister (now Lord Edward Lister as he received a peerage after Johnson’s departure from Downing Street) to help him out and become chief of staff and deputy Mayor overseeing planning. If he wanted to put in charge a man who was labelled “property developers’ favourite lobbyist”, used to befriend the largest building conglomerates, and experienced with forcing through massive transformations, the former leader of Wandsworth was the man!

Reading again the notice released by Wandsworth Council in 2011, we cannot avoid noticing the irony of the part lauding the talent of the former Council leader:

“With specialist knowledge of planning, Cllr Lister is ideally placed to advise the Mayor and ensure the right balance is struck between much needed development and respecting the city’s skyline and character.”

To manage such a description of a man who not only supervised the grabbing of a large part of London by foreign investors but was also instrumental in encouraging the erection of luxurious flagships for the super-rich, while reducing the construction of truly affordable properties for the normal London population, is quite a “tour de force”.

Data from the London Annual Monitoring Report for 2011 (p94) shows that only 11% of affordable housing was built in Wandsworth from 2007/08 to 2009/10, when Edward Lister was Leader of the Council. It was by far the lowest amount of social housing provided from all the boroughs in London (except City of London where there is no data available at all). The average for the rest of London was 54% of social housing amongst the affordable housing supply, for the period.

And Channel 4 News FactCheck found that when he was in charge of planning while Boris Johnson was Mayor of London, the provision of homes let as “social rent”, or the almost-identical “London Affordable Rent”, fell from more than 10,000 a year to around 500 between 2009-10 to 2016-17.

The Guardian reported that Lister told them he was “passionate” about social rented homes. Maybe he was talking about another area, another city, or another country. Or maybe it was an aspiration that he wished to fulfill in another life? The reality is that Wandsworth lowered the obligation to provide affordable housing in new constructions in Nine Elms and later changed its planning rules from 33% to only 15% (Core Strategy 2014 – 4.181).

The trend continued after he left the Council in 2011 to supervise London planning strategy. And while local planning policies were advocating a provision of 60% of social homes within the affordable requirement, Wandsworth decided that until 2019/20 it would be acceptable to do exactly the opposite, lowering even further the number of social housing available.

- Read our article: Does Wandsworth lie about its record of affordable housing provision?

While working with Boris Johnson in Downing Street, first as chief strategy adviser when Johnson became PM, then business liaison chief and chief of staff for the Prime Minister’s office after the departure of Dominic Cummings, the Financial Times revealed in 2021 that he continued as director of an advisory business called Edward Lister Consultants, as an adviser to property group Delancey and as a non-executive director to Stanhope Holdings (commercial office developers).

He was apparently ignorant of the concept of conflict of interest as he told the Politico website that his private sector roles for Delancey and Stanhope were merely “a couple of other bits and pieces” with “very light” responsibilities (but one can imagine highly remunerated).

The Sunday Times claimed in February 2021 that Edward Lister was instrumental in discussions about the construction of diplomatic premises between China and the UK during his time as a non-executive director at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (2017 and 2018, when Johnson was Foreign Secretary). The Daily Mail reported that he acted on behalf of the UK Government while simultaneously working as a paid consultant for American commercial real estate giant CBRE representing Beijing and also being paid by London property firm Delancey, who owned the Royal Mint Court that eventually China bought for £255million. Both property companies said that he was not involved in the transaction.

His ties with Chinese investors are not a secret if we consider that most of the developments in Nine Elms, the large area designated for development on the East of the Battersea Power Station up to Vauxhall, have started with Chinese and more generally Asian and Middle East money.

In 2021, PoliticsHome revealed that Lister was also a director of Eribi Holdings Limited in October 2018 (and until July 2019 when he joined Downing Street), a firm that was aiming to build a “Hong Kong” in Libya, while at the Foreign Office. In this case also, Lister commented that he had “never ever had any discussions with anybody in government about Libya at any time“.

It is usually the case that individuals who enter government resign from their business interests, or at least put them on hold in a blind trust. Apparently, it did not occur to Edward Lister that it would be a good idea to follow the practice.

Nine Elms was one of Lister’s babies that he worked on in his last terms as Mayor in Wandsworth and supervised a deputy Mayor of London. For a number of years, he was first chairman then a member of the Vauxhall Nine Elms Battersea Strategy Board. The board comprises major landowners and developers, the GLA, and Wandsworth and Lambeth councils.

- Read our article in 2021: With Chinese property developers on the verge of collapse, Nine Elms could become Wandsworth’s nightmare

Until 2013, Chinese developers Dalian Wanda was one of the most aggressive overseas investors. Wanda owned the One Nine Elms mixed-use project directly adjacent to Nine Elms Square but struggled to make progress on construction on that project. R&F, another Chinese property developer based in Guangzhou, took over construction but ran also into financial difficulties and had to borrow £750m from its chairman and its CEO by the end of 2021.

The Ram Brewery is another example of a project that Lister pushed through when he was leader in Wandsworth. While he got it approved by the Council, unfortunately, local societies managed to have it called in by the Secretary of State, and one of the biggest public inquiries organised in London for more than a decade took place. Eventually, the plan was rejected, but the Council managed to approve a new and similar proposal in 2013 with a 36 storey tower. This time it was meant to be ratified by Boris Johnson as Mayor of London but he was on holiday. Therefore, a delegation was given to the Deputy Mayor & Chief of Staff… Edward Lister. The Greater London Authority denied any conflict of interest and said:

“As Sir Edward Lister was Leader at Wandsworth Council at the time of the previous application he was fulfilling a different role to that of Deputy Mayor and Chief of Staff at the GLA. In any event, in this particular case we were satisfied in reporting this to him that he has not previously fettered or prejudiced his role in any way.”

At the time we published a graph showing Lister’s involvement at the different steps of the planning process.

The year after, the site was put on sale by Delancey (yes, the company that that Lister joined as board member in 2016 while he was deputy Mayor in charge of planning and later paid as an advisor) and was bought out by Greenland Group, the giant state-owned Chinese property developer but put on sale again in 2021, raising concern about the future of foreign property investments in the UK.

Towards the end of his period as Boris Johnson aide in Downing Street, he was involved in shaping planning policies changes announced by the government, giving to developers more control over planning and stripping out the rules that slow down and obstruct house-building while restraining the possibilities to object. In May 2021, The Mirror reported:

“Boris Johnson’s former top aide Eddie Lister was involved in discussions on a massive shake-up of planning laws despite being employed by two major property firms, it is claimed.”

Ed Lister admitted participating in the meetings but denied he was a key architect of the plans.

Many suspicions of corruptions have also been reported in newspapers. The Guardian wrote that in 2011 Edward Lister helped progress a 34-storey luxurious tower in Paddington from European Land & Property, owned by David and Simon Reuben, the second richest family in the UK, and ratified the redevelopment of Millbank Tower in Westminster by the same brothers in 2016. In November 2019, the Conservatives received £200,000 from the brothers’ company. In total, The Guardian claimed that property developers associated with significant construction schemes approved during Edward Lister’s tenure as Deputy Mayor in charge of planning in London have contributed nearly £1 million to the Conservative party in 2019, just before the general election.

London skyline used as bank safety deposit boxes for Middle East and Asian investors

In 2016, St George Wharf tower was labelled the symbol of the housing crisis. The Guardian provided stark information with the header: “Tower underoccupied, astonishingly expensive, mostly foreign-owned, and with dozens of apartments held through secretive offshore firms“. They reported that 131 out of 210 apartments, for which title deeds were available, were in foreign ownership. Other owners included a former Nigerian government minister, a Kurdish oil magnate, an Egyptian snack-food mogul, an Indonesian banker, a Uruguayan football manager, and a former Formula 1 racing driver. According to the Guardian’s investigation:

“At least 31 of the apartments have been sold to buyers in the far east markets of Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and China; 15 were sold to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates; and others were sold to buyers in Russia, India, Iraq, Qatar and Switzerland. About 15 more appear to have been sold to foreign buyers from China, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Nigeria“.

The influence of foreign investors is so prominent in London that while the architecture magazine Building Design wrote “Livingstone looks set to go down in history as the man who turned London into Shanghai-on-Thames“, Nine Elms was nicknamed “Dubai-on-Thames” by many.

Some owners of St George tower told the Guardian that they don’t spend more than two months a year in the flats, which are empty the rest of the time. In 184 of the tower’s apartments, no resident was registered to vote in the UK in 2016. Six years later, following an electoral reform where Nine Elms became a separate ward electing 2 councillors, meant to be proportionate with the population of similar wards, it is easy to compare: In Lavender Ward, you needed nearly 1400 to be elected, in South Balham you needed 1500 votes but in Nine Elms 328 was enough; all those wards are meant to have the same population and elect 2 councillors each.

When you consider that in Nine Elms, where about 20,000 predominantly luxurious high-rise apartments are built or in their finishing construction stage, the voting population represents a tiny percentage of other areas, it seems inevitable to question the way this planning strategy was aimed at solving the housing crisis for Londoners.

In reality, serious architects and planners know that there are many ways more efficient than towers to increase density and provide more homes. Paris has very few tall buildings (you can nearly count them on the fingers of both hands, if you exclude the recent constructions on the outskirts). However, this is one of the densest cities in the world.

There are still areas to be protected but Central London seems hopeless

In the future, you will still have historical corridors and a view of the Tower of London and St Paul’s Cathedral. But it will not be from a bridge or on land; it will be from the sky, the view from one of the skyscrapers (and with the sharp competition, one of the tallest only to avoid any risk).

The battle on size seems lost in Central London, and the iconic London skyline may be definitely ruined. Nevertheless, there are still parts of London that could still be protected from careless property developers.

One immediate example that comes to mind is the recent proposal of the tower likely to exceed 38 storeys that is currently proposed for Battersea Bridge. Apparently, humans have short memory, or at least that is what many politicians bet on when they make promises. However, one should always remember that recent examples in London show that one tower never comes alone, and it is just the outpost of a cluster, if not a forest of tall buildings, some even bigger than the initial approval that was used as a justification.

When councillors have to make a call on plans involving a tall building, and this one especially, they will have to remember that they are not just approving that one tower but all the skyscrapers that will come afterwards, while trashing completely the planning rules that they defined for the area.

Read our article: Critical Decisions Ahead: Is Wandsworth Labour serious about planning rules?

In May 2014, I contributed to the London Skyline campaign and featured in the Architects’ Journal as Letter of the Week (edition 02/05/2014). I wrote:

“[…] If anything is permitted for the (potential and subjective) “overall benefits”, what is the point of spending so much time (and money) in planning frameworks and local and national rules? Let’s officially declare London an open land available for architects to create their own “signature” buildings disregarding of the heritage, the environment and the local communities.”

With a gloomy mood, I will now take some holidays to reflect on my prediction of nearly 10 years ago and I wish you all a very good end of the year. See you in 2024!