After years of delays and controversies, private developer Taylor Wimpey exits Clapham Junction’s regeneration project. The Council now faces critical decisions about the future of the estate as only a small fraction of planned homes have been built.

15-year project, a flagship scheme for Clapham Junction plagued with controversy, and voilà. The controversial redevelopment of Winstanley and York Road Estate is in limbo as the private partner that championed a total transformation of the initial consultation is no longer involved in Winstanley and York Road estates redevelopment.

A Project Off Track

As of 2025, according to the schedule presented in 2018 by the joint venture between Wandsworth Council and Taylor Wimpey, 60% of the redevelopment should have been completed, with the penultimate phase well underway.

It took some time for the stakeholders to acknowledge that nothing was happening as planned, but eventually at the Housing Committee of 22nd January, the end of a 15-year saga of controversies was officially brought to an end with the official announcement that Wandsworth Council and Taylor Wimpey part ways over Winstanley and York Road estates project.

- Read our article published in 2021: Déjà vu: The Winstanley and York Road regeneration plans in trouble

In reality the decision was negotiated in the autumn and the transfer of Taylor Wimpey’s interest in the Winstanley and York Road Regeneration LLP (the JV) was concluded in December 2024, but kept secret.

Paul White, Chair of the Housing Committee, described the moment on his blog as a “momentous evening”:

“A momentous evening at Town Hall Wandsworth on Wednesday 22nd January 2025, after Taylor Wimpey (developer), “walked away” from the Joint Venture, charged with the Winstanley Estate Regeneration.”

This version of events diverges significantly from the officer’s report, which stated that the split was not initiated by Taylor Wimpey but was instead a strategic decision by the Council “to enable faster progress to be made towards delivering the scheme and its benefits“.

When contacted for clarification, Councillor White declined to answer specific questions and simply reiterated:

“What is true, is that Taylor Wimpey have walked away from the development, as they are no longer involved in any redevelopment at the Winstanley.”

However, other sources within the Council suggest a different picture: “They were paid to go, rather than walking,” said one, adding that the payment “wasn’t single-digit millions, but into the double digits.”

Taylor Wimpey’s own 2024 financial report reflects this departure, recording a £13.6 million net loss as an exceptional cost—approximately 13% of their financial contribution to the joint venture, with a total investment in the Winstanley and York Road regeneration project of about £105m. Still, this loss represents a small fraction of the £339m in dividends paid to their shareholders.

During the Housing Committee meeting, concerns were raised about the opaque nature of the joint venture’s dissolution. What was the actual amount paid to terminate the agreement? Officers cited “commercial sensitivity” as the reason for withholding this information and maintained that the split was part of a Council-led push to “accelerate delivery of the scheme and the new homes and other benefits that will arise from it.”

This discrepancy raises important questions. Does this narrative mask earlier failures by Council officers to respond to known issues and community opposition during phase 1? Or is it simply a recognition by the current Labour administration that the project, as conceived, is no longer viable—and that it would be wiser to focus on delivering the affordable elements that can still be salvaged?

A project adrift and residents in limbo

Taylor Wimpey’s annual report seems to support the latter interpretation, indicating that the Council’s decision “to prioritise the delivery of affordable housing provision” led to a mutual agreement for the developer to exit the joint venture.

Whatever the cause, the outcome is clear: the original regeneration scheme has stalled after phase 1. To date, just 139 homes have been built, in addition to the relocation of a church and school during phase 0. The masterplan was intended to deliver 2,550 mixed-tenure homes—meaning that just over 5% of the planned units have been completed in eight years.

Despite Taylor Wimpey’s exit, the legal structure of the joint venture has been kept alive—likely to avoid disrupting existing contractual obligations for ongoing construction.

Originally set up in 2017 with equal shares between the developer and the Council, the joint venture now consists of 99% Council ownership, with the remaining 1% held by a new company … established by the Council. The directors of this company are appointed by the Chief Executive in consultation with the Leader of the Council.

The Council initially funded the first £150 million of the scheme to replace social housing, with Taylor Wimpey expected to contribute to further development. Their departure now leaves the Council solely responsible for funding the remaining works.

A member of the Council remarked: “With one less player, there should be less delay, hassle and negotiation.”

Amid these legal and financial manoeuvres, the biggest casualties are the residents. A lack of clear and open communication has left many tenants and leaseholders in limbo. In mixed-tenure blocks, residents are already contending with worsening conditions, delayed maintenance, and difficulties selling their homes due to the ongoing and uncertain regeneration.

Without decisive leadership and a transparent plan for the next stages, residents are left in the dark—struggling to make long-term decisions about their homes, their finances, and their futures.

What’s next?

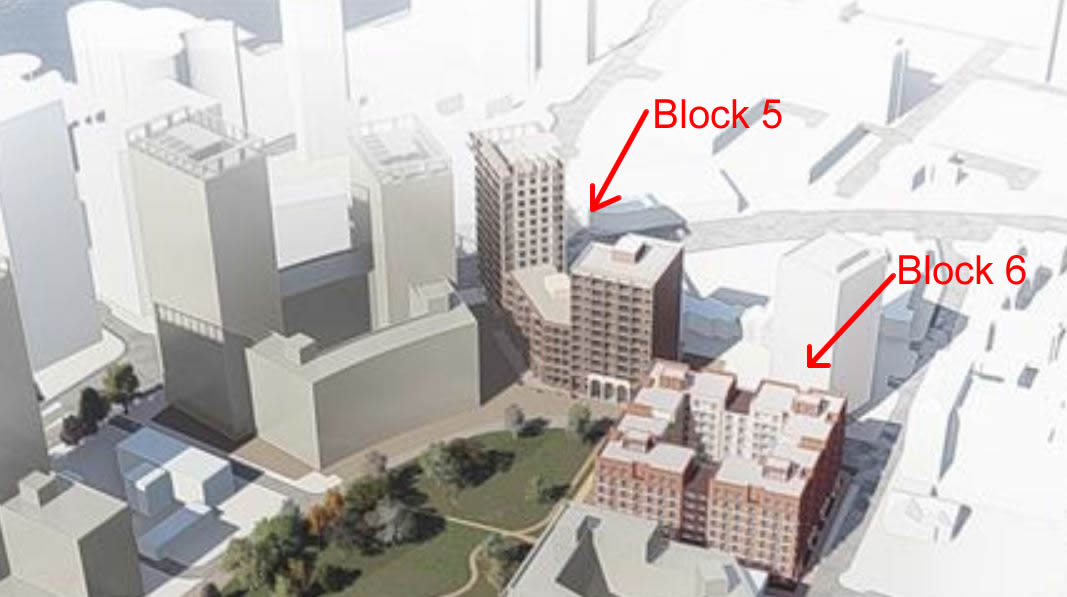

The Council plans to complete Blocks 5 and 6 with existing funds and may seek additional financing if necessary.

Block 5 is nearly finished, and allocations are underway. It will provide 126 additional council homes and allow for the relocation of tenants and leaseholders from Scholey House, Kiloh Court, Jackson House, Arthur Newton House, and Baker House.

The officers are proposing to review the initial phasing of the project and call phase 1 the achievement of block 5, with block 6 making phase 2 with a potential phase 3 to build block 7 … “completed by summer of 2028 enabling a start on site of the first element of the remainder of the regeneration scheme by October 2028“, according to the report.

However, given that only 4 of the 17 planned blocks have been completed (including phase 0 with 3 separate blocks) in the last five years, this timeline appears overly ambitious.

In the meantime, the Council plans to use the vacated properties in Scholey House, Kiloh Court and Jackson House as Temporary Accommodation. They could also use Arthur Newton House and Baker House buildings for the same purpose as the new block 5 will welcome the current occupants. However, considering the cost of refurbishing and reletting, the Council followed the recommendations of the officers to demolish the blocks and provide additional space for the park. The estimated cost of the work to demolish these buildings and create the new park is approximately £700,000.

Lessons from the Alton Estate

In 2022, during the local election period, campaigners against the existing plan for the redevelopment of the estate questioned the position of Wandsworth Labour. Tony Belton, now chair of the Planning Committee, responded that it was the “legacy of the Conservatives” and we had to live with it. Six months before, Aydin Dickerdem (now cabinet member for Housing) commented that while there was a possibility to change the original redevelopment plans for the Alton Estate, the situation was much more advanced for Winstanley and York Estates.

Last year, we noted that the project was entirely off track and could stretch beyond 2040.

The failure of the Winstanley project echoes that of the Alton Estate redevelopment, originally a joint venture between Wandsworth Council and Redrow. Redrow exited London developments in 2022, citing rising costs and planning delays.

The original Alton plan attracted profound concerns from a number of parties since the beginning in 2012. In July 2019, the Putney Society sent particularly strong objections to the masterplan planning application. The Society said that “the starting premise of ‘regeneration’ that the existing buildings are unfit is unproven” and that the main problem is the lack of maintenance by the Council that has let the buildings degrade to justify their demolition.

With Labour now in control, the approach to redevelopment is shifting. Councillor White emphasised that “Council estates were designed for council homes,” and the Alton Estate plan has been revised to include at least 58% council housing—far higher than the Conservatives’ original 23%.

White’s blog suggests the Council may reconsider the entire Winstanley project, stating:

“We are free now, as with the Alton Estate, to plan a new development on the Winstanley Estate, in Battersea, directing builders, as with the Alton Estate, to do our bidding, for the greater community good and not for big corporate profits and others, gaining from large-scale developments.”

A new broom sweeps clean! The Winstanley Estate, in Battersea will see a new People-first vision replace a profits-first approach, as developer “walks away” from the Regeneration Joint venture.https://t.co/brwLZX12t7

— Paul White (@TootingPaul) January 27, 2025

Will there be a new consultation? How will the Council work with the community to avoid repeating past mistakes? It may be too early to say, but early signals are not promising.

In response to our query, the Council stated: “The plans were widely consulted on and supported by the council tenants who lived on the estate.”

- Apparently not so supported: Occupy York Gardens

However, this interpretation overlooks the nuance—and controversy—of the original consultation. As our previous analysis revealed, only 57% of the residents supported the plan involving full demolition. Among non-Council tenants, support dropped dramatically: only 20% were in favour of full demolition, while 60% expressed support for a minimal-disruption option.

Presenting the outcome as broadly supported by “residents” by focusing solely on Council tenants is, at best, a selective—and arguably misleading—representation of the reality.

The support for option 3 depends highly on who has been surveyed: York Road residents or Winstanley residents? Council tenants or private owners?

- More information on the initial consultation: Full demolition for Winstanley and York estates as the chosen option

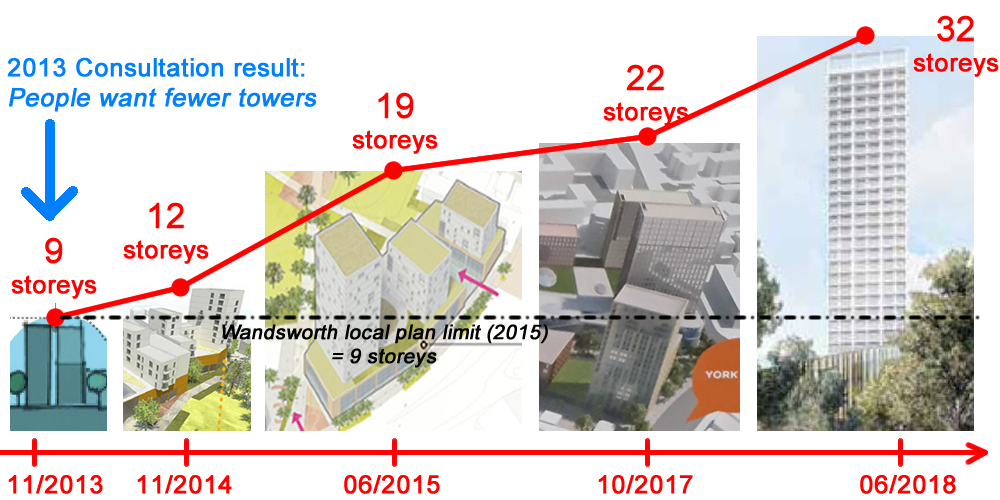

And what about the initial consultation where, according to the booklet produced by the project teams-open-day-exhibition-boards in 2013, the number one thing that residents wanted to change was: Improved homes with fewer towers.

The Council added that “the community will continue to play an important role as we move ahead,” however, in view of their previous statement, their definition of “community” is questionnable.

The need to review the entire remaining masterplan

To mitigate the project’s failure, the Council is investing in local initiatives, echoing a 2021 response to delays in the leisure centre development.

- Read our article: Community benefits to mitigate construction chaos on York Gardens

Proposed measures include funds for a sensory room in Falconbrook School where respite could be provided from noise and disturbance, and improvements to the playground. They also mentioned new additional seating, improvements to play facilities at Ganley Court and support for local voluntary and community organisations such as Providence House, KLS, Waste Not Want Not, Mayors Charity, WOW.

Nevertheless, the initial budget for these initiatives no longer exists, and the suggested £535,000 in funding is highly uncertain. Therefore, both in terms of funding and vision, the project appears to be entering uncharted territory.

At present, there are no rehousing plans for Shephard House, Gagarin House, Chesterton House, and Ganley Court, representing one-third of those originally scheduled for relocation. This could remain unresolved “until a masterplan review is complete“.

Yet, officers insist a full redevelopment masterplan will not be restarted. They are very clear: “A new masterplan is not proposed“, while defending the redevelopment of the site with increased density.

However, they also acknowledge that “the level and tenure of affordable housing proposed in the approved masterplan is no longer compliant with Council policy“. The new Labour administration is currently amending housing policies to require at least 50% affordable homes in new developments and prioritise genuinely affordable housing, with a 70/30 split favouring social rent. The Winstanley and York Road estates’ redevelopment was only offering 35% affordable by unit number.

- Read our article: Make Wandsworth more affordable: the big task of the Council

Wandsworth has 4,000 households on its social housing waiting list, making affordable housing a pressing issue. However, large-scale redevelopments like Winstanley affect the entire community, not just current residents. The previous Conservative administration largely ignored this, with Labour also offering little resistance at the time.

Now, Labour has the opportunity to pause, consult widely, and create a scheme that truly serves Clapham Junction. However, at the January Housing Committee, councillors focused on minor project details rather than addressing the core issue: acknowledging the failure of the original plan and committing to a more inclusive, community-driven approach. A new update is expected in June, but will it introduce a bold new vision or merely tweak the existing plan?

The Battersea Society declined to comment.

ERRATUM: Unlike originally stated, Wandsworth Council did respond to our questions after 8 days with only a few sentences. The article has been modified to take them into account.